Please note: I am guitarist and musician, not a doctor. If you think you might have focal dystonia or if you are experiencing any symptoms of focal dystonia, please consult a qualified medical profession.

Can you recover from musician’s focal dystonia or task-specific dystonia? I was diagnosed with focal dystonia (FD) in 2015. I hesitate to say that I have recovered, but for sure, my symptoms have changed, sometimes gradually, sometimes dramatically, over the last 8 years. By sharing my experiences, I hope I can offer some hope to others who might be going through this.

By the time I was officially diagnosed, I had gradually, over a couple years, lost much of the dexterity in the fingers of my right hand, especially in my ring finger and pinkie. Eventually, complex movements, like typing or playing the guitar, with my fingers and even with a pick, and routine actions, such as tying my shoes or buttoning a shirt, would trigger an involuntary response that would cause my fingers to curl and tighten into the palm of my hand.

The diagnosis was not a surprise. Concerned about my deteriorating dexterity, I had researched and read all I could find online about FD-the onset of mysterious symptoms, that it’s a brain/neurological disorder, and the most devastating aspect of it, that there is no cure. Still, I tried everything I could resolve my condition-wrist and elbow braces, acupuncture, dietary supplements, massage treatments, mirror therapy, Feldenkrais sessions, chiropractic adjustments and more-nothing helped. Some things seemed to make the condition worse. At one point, a neurologist determined through a nerve conduction test that I had developed cubital tunnel syndrome. I followed his advice to the letter, and although the nerve compression issue he detected was resolved, the FD symptoms remained.

Eventually, a doctor referred me to a hand therapist. She realized that I had developed tendonitis-both golfer’s elbow and tennis elbow-in my right arm. The treatment she recommended included mild stretches and exercises to increase blood flow and applying alternating heat and cold to my forearm to reduce swelling. Since, it can take several months to heal after a severe case of tendonitis, my recovery was slow. The tendons at my inner elbow were stiff and visibly inflamed. There were times when it felt like couldn’t even sense my right hand and arm. At one point during my treatments, the topic of focal dystonia came up. I don’t remember which one of us brought it up, but she had heard of it and was interested in helping me enough to do some research. She tried making some splints and suggested alternative treatment options, however, the FD symptoms did not subside, and she ultimately referred me to a neurologist who specialized in FD. It was from this doctor that I received my official diagnosis.

The office visit with the FD specialist began with a physical exam. He performed what I suppose are the most very basic neurological tests to check for imbalances or strength deficiencies. I had done so many of these tests with previous doctors that I started to call them the ‘pull my finger test’. After that, he simply had me demonstrate my symptoms by typing on a computer and from that, and a discussion of my symptoms, he concluded I had FD. I was surprised that there were no imaging or nerve conduction tests and that he didn’t seem concerned or interested in the fact that I had a history of tendonitis or nerve compression. It felt like he simply assumed that I had FD, or perhaps he didn’t expect to find any physical anomalies.

Even though I wasn’t surprised by his diagnosis, it was still devastating. He told me that there was no cure, but said he could try to temporarily relieve the symptoms. The next step would be further evaluations, followed by botox injections into my forearm to prevent the offending muscles from activating. I left feeling hopeless, having exhausted all possibilities for a cure. On the long drive back home I had time to reflect on the appointment and on all the years of mental anguish that brought me to that point. As much as I wanted relief, I couldn’t justify the cost of the procedures plus the cost in terms of money and time of traveling for treatments for a solution that would, at best, provide only a temporary solution. By the time I returned home, I decided to decline treatment and instead continue with physical therapy to at least resolve the tendonitis.

I can’t say exactly when my tendonitis was resolved. It was a slow, gradual process during which I would occasionally notice that my elbow wasn’t as stiff, or the swelling had gone down. In the years before and after my diagnosis, I was studying music theory as a graduate student. Following my diagnosis, I focused more on my classes and began writing my thesis. I had to learn to type with my left hand and one finger of my right hand. After finishing my coursework and starting work on my thesis, I would occasional pick up my electric guitar. I realized that I could play with a pick without any symptoms. This gave me hope that there was a way to somehow reprogram my brain and recover.

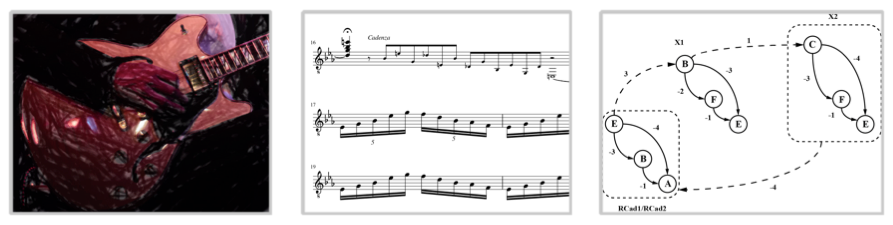

Following my graduation in 2017 and wanting to do more with music, I decided to start composing for guitar, applying my newly acquired skills in music theory. This was not easy, since I was writing for classical guitar and my hand still did not work properly. But as I composed every day using just my thumb and index finger, I discovered that I was able to do use more and more techniques without activating my symptoms. I still could not type or tie my shoes, but something was changing, albeit very slowly.

Over the next several years, I had been consistently composing, arranging and practicing and occasionally performing on electric guitar, but the FD symptoms still persisted without much change. My dexterity seemed to improve a bit in general, but I can’t say if the symptoms had improved or I had just unconsciously avoided the actions that triggered them. I managed to adapt and play with my thumb and index finger, but I could not play anything that required the use of my middle or ring fingers. Once in a while, I would be inspired to attempt to relearn classical guitar and retrain my hands brain and hands, but all of my retraining efforts failed.

Last spring, however, I decided that I wanted build a repertoire of performance pieces, while adapting my right-hand fingerings, as needed. At the same time, I started to retrain my fingers, but took a different approach. In my earlier retraining attempts, I tried relearn from scratch, playing simple scales or arpeggios very slowly and then repeat them at faster tempos. This never worked, presumably because I would eventually reach to tempo or conditions that would trigger my symptoms. When I began my new approach though, I somehow realized there were two components of my dystonia-one, the feeling or sense that I was about to trigger an involuntary reaction, and two, the involuntary reaction itself. I discovered that I could consciously isolate the first component, the sense of an impending involuntary movement, and avoid the second, the involuntary movement itself.

Here’s what I tried. Let’s say, for example, that I am working to play quarter notes on the guitar by alternating my index and middle fingers at a certain tempo using my index finger to play on beat 1 and my middle finger to play on beat 2. My index finger can easily play a note on beat one, but if I begin to sense that a move towards beat 2 is about to trigger an involuntary movement, I stop, consciously relax and let the feeling dissipate, then finally play the next note with my middle finger. Then, I continue on to the next beat 1 and start the process again. If using a metronome, the played notes may not sound like steady quarter notes and might even sound staggered, or more like a dotted-quarter and eighth note rhythm. The important part of the exercise though is not the steadiness of the rhythm, but the fact that link between the sensation and the involuntary finger movement is broken. Once I started doing more of this consistently and with other finger and string combinations, my recovery sped up, and my playing improved considerably within a couple of months.

At this point, I am essentially performing classical guitar without any FD symptoms. I hesitate to say that I have completely recovered, since there are times when my fingers feel a bit unstable, but I feel I am performing even better now than I did before I developed FD. Although I tend to avoid pieces with extensive arpeggios or arpeggios requiring certain fingering (repeated p-a-m-i, for example), my repertoire has expanded beyond what I thought I could do before. Not only has my guitar playing improved, but I can type again and perform daily tasks without triggering any FD reactions.

Here are some suggestions to maintain healthy practicing:

- Avoid injuries by practicing efficiently.

- If you notice any recurring pain in your arms or hands, stop and take an extended break or seek medical attention.

- Be mindful as you practice and avoid tension when working on difficult pr technical passages.

- There are other way to improve your musicianship besides practicing: study music theory or music history, study scores, listen, compose, learn to improvise, sing.

- If you think you might be developing focal dystonia, stop playing and seek help from a medical professional to identify and resolve any physical ailments like nerve compression issues or tendonitis.

- Do not neglect your mental health. The stress of focal dystonia can be overwhelming without support.

Be well!